Perhaps the ultimate irony of Muslim faith in the public sphere was that of Muhammad Ali. The fighter formerly known as Cassius Clay controversially converted to Islam, then protested the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector.

Perhaps the ultimate irony of Muslim faith in the public sphere was that of Muhammad Ali. The fighter formerly known as Cassius Clay controversially converted to Islam, then protested the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector.

The complexity of that decision confounded Americans. Some blamed him for refusing to serve his country. As the website This Day In History documents, Ali was penalized in the manner of a high profile figure.

“On April 28, 1967, with the United States at war in Vietnam, Ali refused to be inducted into the armed forces, saying “I ain’t got no quarrel with those Vietcong.” On June 20, 1967, Ali was convicted of draft evasion, sentenced to five years in prison, fined $10,000 and banned from boxing for three years. He stayed out of prison as his case was appealed and returned to the ring on October 26, 1970, knocking out Jerry Quarry in Atlanta in the third round. On March 8, 1971, Ali fought Joe Frazier in the “Fight of the Century” and lost after 15 rounds, the first loss of his professional boxing career. On June 28 of that same year, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction for evading the draft.”

That’s right, his case went all the way to the Supreme Court of the United states, which overturned his conviction for draft evasion. In other words, Ali was exonerated of wrongdoing in his case against the United States. His faith was also vindicated.

In context with America’s troubled relationship with the Muslim religion and its “peace or no peace” controversies, the case of Muhammad Ali bears recognition as a sign that the Muslim faith does have a tradition of peace at its core.

Conscientious Objector

Ali was justified in his argument that “I ain’t got no quarrel with those Vietcong.” The nation entered the war ostensibly to stop the advance of communism. Instead, America’s involvement in the Vietnam War proved far more costly in terms of lives and political capital, and communism ultimately won the battle for control of Vietnam. One could argue that it ultimately lost the war in that communism ultimately collapsed the Soviet Union.

But in the moment, the Vietnam war was unpopular at the liberal end of the political spectrum, leading to war protests and civil unrest. The nation imposed a military draft and thousands of lives were spent on the guerrilla battlefields where victory and loss often felt like the same thing. In other words, a conscientious objector could find many reasons not to want to fight in Vietnam. That’s why Ali did not go to fight in Vietnam.

The ugliness of the fight game

Yet Ali was quite ironically a fighter by trade. He was also prone to controversial methods of race profiling as a means of fight promotion, calling men such as Joe Frazier “Uncle Tom” and engaging in pre-fight dialogue that was profoundly insulting.

Ali: “Joe Frazier should give his face to the Wildlife Fund. He’s so ugly, blind men go the other way. Ugly! Ugly! Ugly! He not only looks bad, you can smell him in another country! What will the people of Manila think? That black brothers are animals. Ignorant. Stupid. Ugly and smelly.”

Ali: “He’s the other type Negro, he’s not like me,” Ali shouts to the now stunned white interviewer. “There are two types of slaves, Joe Frazier’s worse than you to me … That’s what I mean when I say Uncle Tom, I mean he’s a brother, one day he might be like me, but for now he works for the enemy”

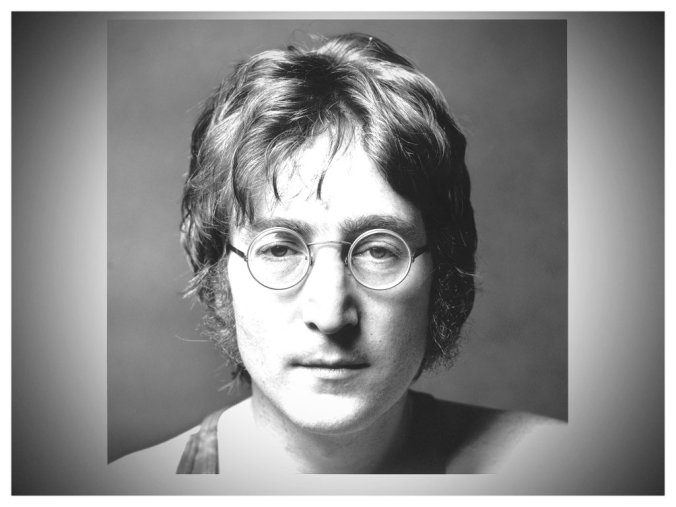

Lennon and Ali

In his violent reproach toward his rivals, Muhammad Ali resembled another public figure of the late 1960s and early 1970s. That was John Lennon, who spoke for world peace even as he engaged in very public fights with his former Beatles partner Paul McCartney. Their friendship for a while became a bitter rivalry.

In his violent reproach toward his rivals, Muhammad Ali resembled another public figure of the late 1960s and early 1970s. That was John Lennon, who spoke for world peace even as he engaged in very public fights with his former Beatles partner Paul McCartney. Their friendship for a while became a bitter rivalry.

But men like Lennon and Ali ultimately did apologize to their rivals.

Ali: “Joe Frazier’s a nice fella, he’s just doing a job. The bad talk wasn’t serious, just part of the buildup to the fight. The fight was serious, though. Joe spoke to me once or twice in the middle, told me I was burned out, that I’d have to quit dancing now. I told him I was gonna dance all night.”

Lessons learned

The point here is that personal rivalry drives public interest, and there are commercial and professional reasons why this is beneficial to the advancement of individual causes. Both Ali and Lennon are considered great artists in their trade. Each knew the value of slogans and sound bites. Ali engaged in a form of street poetry and Lennon lyrically crafted songs that appealed to both the common man and universal themes.

These similarities and differences are interesting to note. Ali advocated a religion while Lennon was equivocal about such matters, arguing through his song Imagine that perhaps even religion had its limitations in terms of seeking better understanding. Yet both seemed to arrive in the same place.

Imagine there’s no heaven

It’s easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us only sky

Imagine all the people living for today

Imagine there’s no countries

It isn’t hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too

Imagine all the people living life in peace, you

You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one

I hope some day you’ll join us

And the world will be as one

It is worth nothing that that the statement by Ali that “I ain’t got no quarrel with no VietCong” could serve as a quick summary of the reasons why Lennon also protested the quasi-religious motives of the Vietnam War.

And indeed, communism was not resisted by conservative Americans only as a social and economic system, but because its “godlessness” was judged to be in direct opposition to the supposedly religious foundations of American history.

But it holds true as well that the most vicious of all wars are not fought over lack of a god, but as rivalries between two competing notions of God.

That is the precise reason why one sect of Muslims is killing another, and why ISIL is so committed to creating a caliphate or national state in Iraq. They are attempting to impose their version of Sharia law by conquering territory and forcing people to either convert of die. The entire enterprise is a rivalry over interpretations of God. As a result, ISIL wants to confront Christianity on its “home soil.”

Ali-Frazier redux

That rivalry over who represents the “real deal” is the the same sort of argument Ali foisted on Joe Frazier, who he openly accused of being the “wrong kind of black.” Their mutual anger over issues like these fueled three killer fights between the two men.

The same brand of story unfolded between McCartney and Lennon, who exchanged critical songs as a means to express frustration with the artistic differences that once made them the most dynamic writing team in popular music.

Religious rivalries

It is the same thing with the Muslim, Christian and Jewish faiths in this world. All share the same root histories, yet the advancing interpretations and judgment on what constitutes a prophet or a Messiah are to this day cause a triangulation of horror, murder and prejudice.

It remains to be seen whether these religious differences can be reconciled or forgiven. Some claim the differences are too fundamental or profound. Others point fingers at the murderous ways of the opponent while ignoring their own egregious modes of death and destruction. This is true of the collective efforts by Christian, Jewish and Musliim states.

Great rivals can become great allies, or at least show respect. Ali sooner or later did that with Frazier, as did McCartney and Lennon.

The rule we need to consider is that the more we share in history and the more we are alike, the more bitter the feud can be.