The history of Christianity is one of argument over the meaning of Jesus, the role of sin in life, and humanity’s relationship to God. Or at least, that’s what Christianity is supposed to be about. Instead, the world has witnessed a protracted conflict over scripture, its authorship and verity, and how we’re supposed to understand critical aspects of the book Christianity calls the Holy Bible.

To understand these questions more clearly, consider that when Jesus arrived on the scene two thousand years ago, he followed in the wake of a man called John the Baptist, of whom there was a supposed prophecy. Isaiah 40:3: “The voice of one crying in the wilderness: ” Prepare the way of the LORD; Make straight in the desert. A highway for our God.” John’s role was clear: cut through the religious legalism of the day and place the focus on repentance of sin. He challenged the rules and rituals of the temple authorities, and Jesus later dismissed them as meaningless to a relationship with God.

We all know what happened from there. The religious authorities took great offense at being questioned. They sent people out to quiz Jesus on the rules they made from scripture, and Jesus tossed revealing questions back at them. They could not answer him effectively because their hypocrisy in implementing those traditions was apparent: they loved the authority it conferred upon them. Jesus also found the use of the temple for commercial purposes offensive. He attacked those conventions by creating a whip out of cords and drove the vendors out of his “father’s house.”

None of this took place because the religious authorities were Jewish. Jesus was a Jew by birth and faith. But he despised what conservative religious authorities had done to turn Judaism into a religion of law rather than love of others. He used parables to instruct people on the ways of God that stood outside the Torah as examples of the right way to live. Most of these stories drew from daily life experiences, and many used organic symbolism: the mustard seed, the yeast in the dough, to draw connections between nature and spiritual truths. That’s a vital example of how we’re supposed to read the Bible. Yet centuries of adherence to biblical literalism and the legalism that emerges from it have buried Jesus’ wisdom and ways under layers of bad theology, defined as defending God when God does not need defending.

Rather than learn from the conflicted nature of the religious authorities in Jesus’ day, the religion known as Christianity repeated its mistakes many times in history. The Catholic Church used purgatory as a money-making scheme based on a Jewish reference to the purification of souls. One of their priests, Martin Luther, challenged this brand of legalism and sought to emphasize salvation through grace.

That led to the Reformation, a religious movement that produced Protestantism, a branch of Christianity that, to this day, many conservative Catholics consider illegitimate. But Protestants went on to invent their form of legalism, which goes by various names, including fundamentalism, biblical literalism, and today’s populist form called “apologetics.”

All of these constitute the most legalistic forms of Christianity. Many focus on “obeying the rules” and engaging in the confessional language of latter-day Christianity. These habits frequently dismiss Jesus’s core teachings in favor of adhering to a set statement of belief encompassed in creeds or, worse, through alliance with political aims of power and authority.

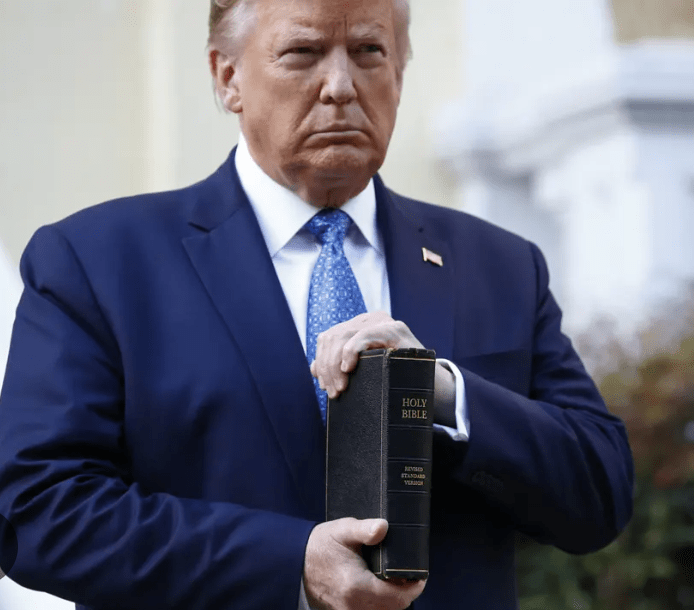

That brings us to the problems facing America today, where politically charged religious beliefs assemble a form of allegiance to God and Country. This approach is collectively known as Christian Nationalism, fueled by the brand of Christianity called Dominionism, a repeat of the same legalistic fascism that religious authorities engaged in two thousand years ago.

When you trace the behavior patterns to their religious sources, it’s easy to comprehend. The Serpent in the Garden of Eden sought to take Adam and Even under its authority and control by quoting God and pretending to defend God’s Word. “Did God say, ‘You must not eat fruit from the trees in the garden,” and then issues the legalistic half-truth that leads the couple into sin, “You will not surely die.”

See, the Serpent “was more clever than any of the wild animals the LORD God had made.” It knew how to manipulate people to take them under its authority. It tempted them with promises of knowledge and authority, stating, “God knows that when you eat fruit from that tree, you will know things you have never known before.”

Where do we find that type of temptation repeated in scripture? Satan tempts Jesus in the Wilderness by inviting him to use power and create bread to assuage his hunger or to submit to Satan’s authority and earn all control over the world. See, the temptations of legalism have always been with us. It’s sad that Christianity so often succumbs to its own worst flaws and then tries to impose them on the world. That’s what we’re facing in the United States of America: a religious mindset that assumes it owns all authority but ignores the corruption at its core. That belief system is easily exploited by those who excel at manipulation and seek power for themselves, historically, theologically, and politically. Jesus didn’t like or abide by any of that.

I’m the author of the book Honest-To-Goodness: Why Christianity Needs A Reality Check and How To Make It Happen. You’ll find solutions to the problems caused by legalistic Christianity, and ways to confront its many forms in social media, politics, and otherwise.